By Charly SHELTON

When we think of Halloween, we think of witches. The two are inseparable, especially in today’s zeitgeist. But in the cultural fabric of America in 1692, witches were not relegated to late October. They were an everyday occurrence and an ever-present danger. This constant fear led to a series of witch trials across Europe, on ships headed for the New World and then across the fledgling colonies of America.

No trials were more widely heard of, nor better remembered, in this country than the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

The social climate of 1692 was similar in some ways to the climate today. People were easily subject to mania based on information coming from the one and only source they turned to for news (the church then, their favorite news site today), spurred on by a lack of education on the background of the issue at-hand. But the term “witch trial,” which is thrown around today in an almost cavalier attitude to try and discredit any accusation as being merely a baseless ploy at a power grab, is not what the term used to mean. Today’s so-used “witch trial” could see a politician being plastered on the news for a few days. The witch trials of 1692 could see innocent people being hung, crushed to death by rocks, thrown in prison for life or drowned, their only crime having the courage to speak out against those who would wield their positions of power to inflict suffering on others.

The witch trials engulfed the town of Salem Village in Massachusetts into a panic in the spring of 1692, and it started with the illness of two young girls.

Betty Parris, age 9, and Abigail Williams, age 11, became sick – bedridden and catatonic with outbursts of violent fits and uncontrollable screaming. The local doctor, William Griggs, diagnosed them with bewitchment. A study published in Science in 1976 found that the fungus ergot, which is found growing in rye, wheat and other cereals, could have been the culprit in inducing the delusions, vomiting, muscle spasms and other symptoms that the girls experienced. Soon after the first two girls were diagnosed with bewitchment, many other girls around the community began to come down with similar symptoms and received the same diagnosis. Salem Village minister Samuel Parris, father to Betty and uncle to Abigail, wanted to know who was to blame for all these bewitchings. When the girls began to recover, they made accusations of witchcraft against the Parris’ Caribbean slave, Tituba, as well as local homeless woman Sarah Good and poor, elderly Salem Village resident Sarah Osborn. Good and Osborn protested their innocence as good Puritan women but Tituba confessed, hoping to save herself from the almost certain conviction at trial by informing on other community members who she said were working with her in service of Satan. This set off a hysteria of accusations, one after another, some hoping to save themselves by shifting blame and redirecting the punishment. Among those accused were Martha Corey, whose husband Giles testified against her and was himself then accused. Martha was hung and Giles was crushed by rocks. John and Elizabeth Proctor, who spoke out against the hysteria and were accused of favoring witches, were accused of being witches themselves.

But not all who were accused were tried. One of the girls testified that she had seen Samuel Willard working wizardry. Willard, the well-respected pastor of the Old South Street Church in Boston, was a pillar of the Puritan community in Massachusetts. Upon hearing his name, one of the judges at the trial said, “No, you must be mistaken,” and had her sent out of court. It was in this way that the magistrates controlled who was ousted and who was saved, depending on their usefulness and their support of the power position they held at the time.

Innocent people were put to death for witchcraft, died in prison awaiting trial, or were killed during experiments to find God’s judgment on them – like by lowering the accused into a lake and, if they floated or swam, they were witches and therefore executed; if they sank and drowned, they were innocent and met God with a clean soul.

In all, 24 people died during the witch trials between February 1692 and May 1693. An additional 140 were wrongfully imprisoned. Even more were accused and, in a society like that, once people were accused, their reputation was tarnished as though they were guilty despite being proven innocent. This could plague them for the rest of their lives, barring employers from hiring them and scaring customers away from their businesses. This makes it an apt analogy for McCarthyism of the 1950s, as used in the 1953 play by Arthur Miller “The Crucible.”

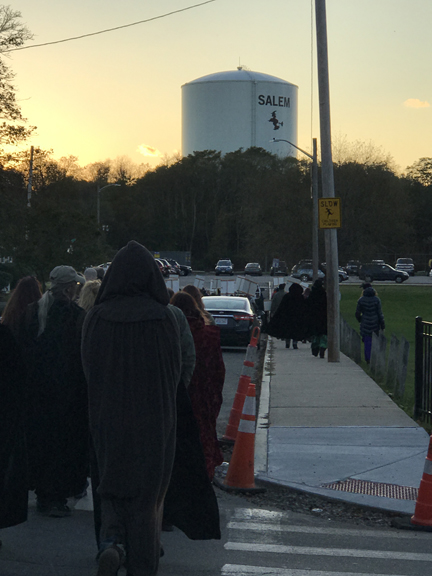

For modern witches, practitioners of Wicca who ascribe to the tenets of earth worship and doing good works for the world, Salem Village (modern day Danvers, Massachusetts) is a central hub of the religion, and the men and women who were put to death during the trials are those who paved the way and started the conversation for the acceptance of actual witches.

“Visiting Salem was soul awakening for me,” said Sabrina Shelton, my wife, who went to Salem last year at Halloween for the Samhain ceremonies on Gallows Hill, where the victims of the Witch Trials were hung. “It was so great to be surrounded by people from all walks of life from all over the world for the Halloween season. Thinking about the Salem witch trials brings up a lot of things for me. The woman in me is angry at the male town elders who swept the town into panic against mostly single or older women. The witch in me is angry at the close-minded zealots who either confused healers for something darker or misunderstood the rituals and beliefs of people different from themselves. But both parts of me can agree that it is a magical place today with all the love that the pagan pilgrims bring to honor this hallowed ground.”