Photo by Mary O’KEEFE

By Mary O’KEEFE

“It is important. It is very important because six million Jews were murdered. They can’t talk. We are the few survivors [who] are left. We have to talk for them,” said Joseph Alexander of why he travels the world to share his story of survival at the hands of Nazi Germany during WWII.

Alexander was born in Poland in 1922. His family enjoyed a comfortable life – family members lived close by – and good neighbors. Then on Sept. 1, 1939 everything changed when Hitler’s army invaded Poland. By 1940 the Nazis had transported the Jews to Warsaw ghettos, which were work camps.

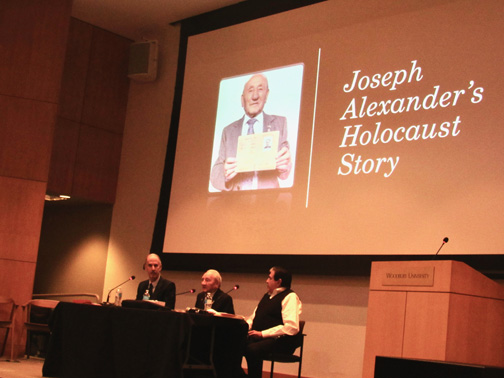

Alexander spoke at Woodbury University in Burbank on Monday. In November he will be celebrating his 101st birthday, but age has not slowed his mission of sharing his story with everyone – and anyone – who will listen.

Dr. Eric Schockman, who hosted the talk at Woodbury, stressed the importance of the story of Alexander’s life; though the invasion may have occurred over 80 years ago the message is as important today as it was at the end of WWII.

“We are seeing signs of swastikas in bathrooms and a resurgence of Nazis marching openly in the streets,” said Dr. Barry Ryan, Woodbury president. “This is the point where we need to stand up … This is the point [when] the future is hitting us in the face. It is here folks. It is not going away. This is the new America and we are hear to listen to the past, learn from it and then move forward so we never forget.”

“My name is Joseph Alexander. I am a holocaust survivor from Poland, and I survived 12 camps,” Alexander said.

Alexander was born in Poland. He said when the Germans entered his village in Warsaw they separated people into restricted and non-restricted areas. A couple of weeks after the invasion, the Germans ordered a group of people to the town square. He is not sure why, but neither the family in his home nor in his uncle’s, both located in the town square, were in this first gathering. Those who were ordered into the town square were “taken away.” There were rumors that the Germans would be coming back to take the rest of the Jews.

“My dad said, ‘We are not going to wait.’ My father had three sisters who lived 25 kilometers [away],” he said.

Alexander’s family got a deep wagon and his mother, father, one sister and one brother packed it up and left the area. Alexander remained at the home with two other sisters. They loaded a second wagon to follow their parents.

He and his siblings went to a little town where things were almost normal but then, two weeks later, he went to his first camp. This was a work camp that allowed people to go home on the weekends. The work was hard; they were digging a canal that involved standing in water without boots that was up to their knees.

Alexander got blood poisoning and couldn’t work. The police came to his father’s door to find him but his father convinced them he didn’t know where he was. He stayed away to heal; this was the time they began to build the walls in Warsaw to create a ghetto.

“[The ghetto] was a very small area. They put in over 400,000 people. You can’t imagine how terrible, how bad it was, there. People were dying on the streets, everywhere,” he said.

He lived in a ghetto for five months. Then came the order from the Germans that all Jewish men from the ages of 16 to 60 were to meet at the school house.

“And off I went to the camp,” he said.

At his first camp he worked to build a dam. The work was hard and prisoners used picks to move the hard and rocky soil. They were given a piece of bread and a cup of coffee in the morning, then worked all day and at night were given potato or spinach soup.

“People were dying so they combined two or three camps into one so I moved again. Then after a while the same thing happened at this camp and I moved again,” he said.

He moved from camp to camp, working at hard labor from roofing to building an airport. He had been in seven camps when a train arrived.

“It wasn’t a passenger train, it was a cattle car [boxcar],” he said.

They crammed 30 to 40 people into each boxcar. The destination normally would have taken five to six hours to arrive at but he said they were in those cars for three days without food, water or bathroom facilities.

“And we arrived in Auschwitz,” he said.

The train stopped and whoever could step out did. Alexander estimated about 30% to 40% of the people who were originally placed into the boxcar had died.

“You would walk out [of the boxcar] and line up in rows of five and that’s where we met Dr. Josef Mengele. He was called [Dr. Death]. He selected people for human experiments or for the gas chamber,” he said.

Mengele was going down the line of Jews, selecting them for two separate lines – one to the left and one to the right. The one on the left were people who were sick, old, very young or weak. Those to the right were healthier. Alexander was chosen to go left.

“I was a little guy so he picked me up to go to the left and if I would have just come from home I wouldn’t have known the difference. But I had been in seven camps,” he said.

Alexander had seen over and over again what happened to those who were deemed weak.

“At every camp I always tried to get in with the big strong men,” he said. “It was after midnight; if it was daytime I don’t think I could have done it, but when Dr. Mengele moved farther down [the line] I moved back to the other side. If I hadn’t moved to the other side I wouldn’t be here talking to you today because the people on the left were taken on a truck straight to the gas chamber.”

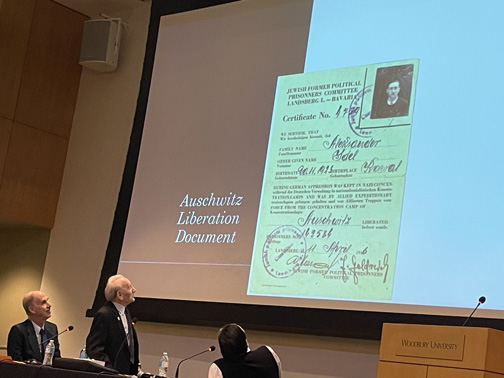

Alexander was in Auschwitz when he received his tattoo, which was used for identification purposes by the Nazis.

“I got a tattoo. From that moment on you had no name anymore. This was your [name]: 14284,” he said, reciting his number.

He worked and was taken from camp to camp. By April 28, 1945, he had been at 12 camps including Dachau. On that day in April he and others he was with in the camp were told they would be going on a march, a death march. They would walk into the mountains in Germany and they would be killed by Nazi soldiers. They walked for two days but during this time they heard the American tanks and witnessed American bombers. One night they were allowed to rest; when they woke up they found the German soldiers had run away. The German police arrived and walked them into a village; then the police disappeared.

“Then we saw an American tank move in and we were liberated,” he said.

But this wasn’t the end when everyone cheered and life returned to normalcy. The Americans created areas for the survivors to stay but Alexander and his friends continued to go to camps that were liberated, placing their names on lists, looking for any family survivors. Only a cousin survived; he still does not know what happened to the rest of his family.

Alexander recently traveled to Auschwitz to walk the camp again. When asked why he would want to go back he said, “Because I am alive and Hitler is not.”