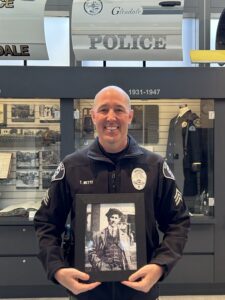

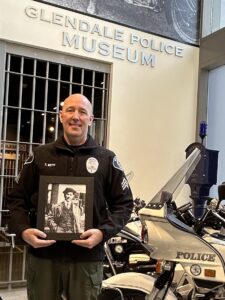

Sgt. Teal Metts, GPD historian, stands with a photo of Marshal Charles Whitney Smith, the first fallen officer in the Glendale area.

By Mikaela STONE

After giving his life in service to the police department in 1915, Marshal Charles Whitney Smith, the first fallen officer of the Glendale area, lay forgotten by the general public in an unmarked grave for about 110 years. Glendale Police Department’s (GPD) Sergeant Teal Metts, GPD historian, knew of Smith from the city’s annual fallen officer memorial. Frustrated that no official picture of Charles existed for Charles to be honored, Metts had hoped to showcase a picture of Smith’s grave at Forest Lawn, only to find an empty plot. The discovery of how little information existed about his fellow first responder inspired him to spearhead a three and a half month plunge into city archives and a fundraiser for Smith’s headstone to ensure the marshal’s memory lived on.

Charles moved to the City of Tropico from Riverside with his wife Mae Gibson in 1912, just six years before the 700 person town merged with Glendale. Smith had a long history of community service, volunteering first with the Royal Arcanum, a non profit in his hometown of Malone, New York, then for Tropico Voter’s Club. Two years later, Tropico appointed him Marshal and City Building and Plumbing Inspector, which made him the primary, and only, professional member of law enforcement in the city. During the nine months he served, he led a posse of deputized citizens in response to the homicide of Burbank Marshal Luther Colson.

Colson was shot and killed in an ambush while on foot patrol on Nov. 16, 1914. The three suspects were apprehended, according to Officer Down Memorial Page.

Colson was shot and killed in an ambush while on foot patrol on Nov. 16, 1914. The three suspects were apprehended, according to Officer Down Memorial Page.

Charles patrolled so often his constituents were hard pressed to find him in his office. On the morning of January 9, 1915, the Tropico Board of Trustees asked Charles to resign, frustrated by his absence. Determined to prove himself, Charles patrolled that evening anyway. Tropico citizen Stephen Haviland soon approached him, having just been robbed at gunpoint by the “Long and Short Holdup Team,” a pair of thieves responsible for numerous robberies in the greater Los Angeles area, for three dollars’ worth of silver—today’s equivalent of $93. Smith gave chase and apprehended one of the two men. Correct in his hunch that the second planned to flee Tropico, Smith found Gilbert Herringa on a Pacific Electric streetcar and began to question him. Herringa shot Smith point blank three times before jumping out of the moving streetcar. Herringa would be caught and shot by Los Angeles County Sheriff John Casper Cline and his posse the following day.

Smith passed away the evening of January 9, 1915 at the age of 42. His last words, spoken to his wife, were “Maybe I made good tonight.”

Finally uncovered, Charles’ story and Metts’ desire to procure a headstone touched the community. Within six hours, the community raised over three thousand dollars for Charles’ grave—including a donor who offered to pay in full. Metts declined that offer in favor of allowing as many well-wishers as possible to contribute. Also inspired, Dennis Vittetow with Forest Lawn contacted Metts with the news that he and his coworkers had searched their archives and found the name of Smith’s wife, buried next to him in the same plot, also unmarked—the first mention of Mae Gibson’s full name Metts had encountered. After her husband’s death, she never remarried, instead choosing to live with her sister until her own death at the age of 76. Forest Lawn paid for Mae’s headstone and waived the setting fees for the couple’s graves.

As for Charles’ beloved Tropico, traces of the city remain if one knows where to look. The infrastructure for the streetcar still remains, another memorial to the place the Marshal was shot. Should one wish to follow the path, the Corralitas Red Car trail follows the concrete remains of the rail line.

The Glendale Police Department plans to hold a ceremony for the setting of the gravestones and to posthumously name Charles a Glendale Police officer; the exact date of that event is yet to be determined. Metts also hopes to name a local park after Smith.

“In [my] eyes, [Charles Whitney Smith] is a hero to the entire area, not just one city,” Metts said.

He added it is important that Charles is not forgotten, so that the entire community can honor a man “who made good.”