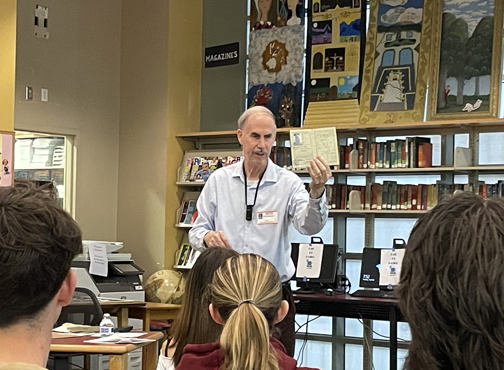

David Meyerhof shares with Burroughs High School students the story of his family’s escape from German-occupied portions of Germany and France.

By Mary O’KEEFE

CVW has been able to interview numerous survivors of the Holocaust. As we have written, reading about history is one thing – but being able to interview someone who was witness to that history is an entirely different matter. The impact of hearing these stories can be seen in the eyes of the students who hear them. These opportunities are because David Meyerhof has made it his mission to have witnesses share their stories of the Holocaust.

Meyerhof’s parents and grandparents, all Jewish, escaped Germany and are Holocaust survivors. He knows the importance of sharing these stories of survival. He often shares with students that history can, and will, be repeated if people do not understand the past and recognize the warning signs for the future.

Meyerhof is a retired math and science teacher. He coordinates the Holocaust Survivor Speaker programs for the school districts of Glendale, Burbank and Los Angeles. He took over this responsibility after Sylvia Sutton, from Temple Beth Emet in Burbank, retired.

Meyerhof is also a poet. His presentation is titled “Escape from Nazi Germany: Nobel Prize to Kindertransport,” which he recently presented to students at Burroughs High School in Burbank.

“I am going to [share] the story of my father [Walter], mother and my grandfather [Otto]. I am going to be using my father’s autobiography,” he said. “These are actually my father’s words.”

He shared the change in his school that his father noticed when Adolf Hitler came into power.

“When a teacher entered the classroom, we had to stand up and give the Nazi salute [and say], ‘Heil Hitler.’ I just moved my lips and did not say anything,” Meyerhof read from Walter’s writing.

This began in 1933 and by the end of that year a Hitler Youth group had formed at his father’s school. One of his fellow classmates was the leader and asked him why he was still at the school. The leader threatened to beat up his father if he returned to school.

“I felt terrorized and turned to my only brother, and he said he couldn’t do anything about it,” Meyerhof continued to read from his father’s book.

The violence and threats were not just from other students, but also from teachers. At one point a music teacher hit his father so hard his nose bled. When Meyerhof’s grandparents complained to the principal they were told he was powerless because the music teacher was part of the Nazi party.

“So imagine if your teacher didn’t like what you were doing [s/he] could come up and hit you and nothing could be done,” said Meyerhof. “That was the condition of [Jewish] students in 1933 Germany.”

His father Walter was able to get through school and traveled to France where he attended college in Paris, France. He was about 18 years old at the time and while he was in college the French began their surrender to the Germans.

All German Jews who were in France, males aged 17 to 65 and females aged 17 to 56, were told to bring a blanket, clothing and food to an area where they were assembling. All the men went to a sports stadium. His father described the unsanitary conditions they lived in while they were held there.

Walter was later assigned to an Army camp in Chambaran, France. The conditions there were not any better and in fact he spoke of soldiers being violent toward him and others.

“[My father] had to march 300 miles south of Paris,” Meyerhof said explaining the French Army conducted the march. “There was a fear of being overtaken by the German Army, which would mean they would have been sent to a concentration camp,” he said.

Walter said the group had to march at night because German fighter planes were strafing anything that moved. He lived in constant fear they would be captured and taken to concentration camps.

Meyerhof shared pencil drawings his father Walter made during the march. The group arrived in the village of La Chambaran where a village school had been turned into a detention camp. His father noticed there was a cave behind the school. He decided to explore and found he could go into the village. No soldier was guarding the back of the school, so he was able to leave. One of his fellow detainees would answer for him every day during the soldier’s roll call. This gave him time to escape and go where his grandparents were.

This is where his grandparents and he met American journalist Marion Fry, who helped anti-Nazi refugees escape France between 1940 and 1941.

Fry was given a list of 200 names, which eventually grew to 2,000. The names were of “intellectuals, scientists, musicians and artists.” His grandparents had asked Fry for help. When Fry discovered Meyerhof’s father Walter had escaped from his detention camp he told him he had to go back immediately. Fry was working on papers that would allow the family to leave German-occupied France; however, this escape would be in jeopardy if it were discovered Meyerhof’s father had left the detention camp.

Walter made his way back to the detention camp and his escape was never discovered. Three weeks later Fry presented forged papers to get him out of the camp. The papers were accepted as real and he was released.

Fry worked out of a hotel where forged documents were created and plans for escape were prepared.

“My father was asked to find a path for the refugees from France across the Pyrenees to Spain,” he said. The Pyrenees is a mountain range between France and Spain.

“On Sept. 6, 1940, [my father Walter] and two of his friends set off to find a path for refugees to escape,” Meyerhof said.

The friends – Lisa and Hans Fittko – would eventually help over 100 people escape German-occupied France. During their exploration, the Fittkos and Meyerhof’s father were discovered by two French border officers who appeared from the woods. The three attempted to convince the officers they were Germans who wanted to escape to Spain, but they were not believed. They were taken to a nearby village and put into prison cells. His father feared again that he would be deported to a German concentration camp. The three spent one night in the prison cells then taken to court, which was a French café.

“You see, in France things were a little bit looser,” Meyerhof said. “Even though they were jailed it was a nice day so [the jailers took the prisoners to] lunch.”

While at the café, Meyerhof’s father recognized a customs officer who his family knew. He had paper in his pocket so he wrote a note to the customs officer explaining they had been arrested and needed help.

They left the café and the next day Meyerhof’s grandparents were in court to support Walter and his friends. The judge, who knew Meyerhof’s family, was also a socialist and anti-Nazi. He heard the border officer’s story, said thank you and released the prisoners.

About 10 months later the Meyerhof family was able to obtain the proper, forged, papers and made their way to Spain. Walter was able to then make his way to America where he became a professor of physics at Stanford University.

Meyerhof’s grandfather Otto was a world famous scientist who won the 1922 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. He received recognition for his discovery of the fixed relationship between the consumption of oxygen and the metabolism of lactic acid in the muscles.

Meyerhof shared his story of how the life of his grandfather as a professor at a university in Germany changed as Hitler came into power. He reminded students that, in a short time, all Jews were kicked out of their businesses, jobs and homes and that many perished due to the Nazis “Final Solution,” which was the government’s program of genocide against the Jews. He also told them to stay aware of what was happening around them because history can – and often will – repeat itself.