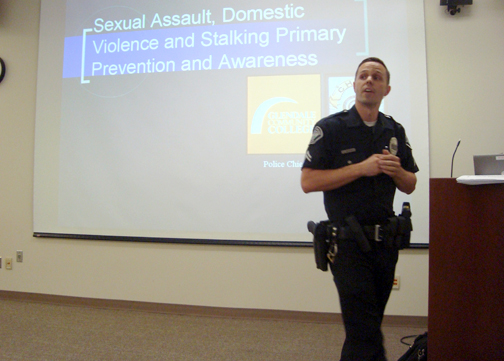

Corporal Neil Carthew, a police officer with Glendale Community College, outlined the responsibilities that college campuses have in providing information regarding sexual assaults during the Campus Safety seminar at the La Crescenta Library on Monday night.

By Jason KUROSU

On Monday night, the same day that GUSD students returned to school, the Crescenta Valley Weekly hosted a seminar at the La Crescenta Library regarding safety issues for prospective college students, many of whom are embarking upon their first college experiences, an equally exciting and vexing proposition for both students and their families.

With universities across the country under scrutiny for their response or lack thereof to sexual assaults on campus, Monday night’s seminar served to inform students of their options for preventing, intervening and handling incidents of sexual assault, as well as other issues for those moving out of their family home for the first time.

Corporal Neil Carthew, a police officer with Glendale Community College, spoke about resources available to students, the latest standards colleges must follow regarding campus sexual assaults and tips to help students look out for themselves and others.

Recent legal changes to California campus standards include Senate Bill 967, which redefined how consent is determined. Colleges must now adhere to an affirmative consent standard, in which consent must be clearly given by both parties.

“Me growing up, it was ‘no means no.’ Now it’s ‘yes means yes,’” Carthew said.

This eliminates a number of scenarios from being construed as consent, including inability to communicate verbally or otherwise, lack of protest, lack of resistance, silence or the existence of a dating relationship. Affirmative consent is also defined as an ongoing process, during which consent may be given and then later retracted.

Universities that receive federal financial aid funding must also adhere to the Clery Act, named after Lehigh University student Jeanne Clery, who was raped and murdered in her dorm building in 1986. The Clery Act holds universities to disclosing crimes committed on or near their campuses, with penalties for schools that do not share this information with the public. Recent changes to the Clery Act include added requirements such as prevention awareness programs for incoming students.

Criminal charges need not be pursued for colleges to take action against a student suspected of sexual assault. Internal investigations can be conducted by university administrators simultaneously with law enforcement investigations, with suspension and expulsion among potential sanctions.

Among the prevention strategies that Carthew suggested was that students do things as part of a group, whether going to parties or walking home from class. Students were also urged to coordinate with friends and family, letting them know who, when and where they are dating and to have signals with their group of friends, should one feel uncomfortable during any given situation and need to leave.

But the prevention strategies discussed were not limited to one’s own wellbeing. Bystanders to potential sexual assaults often do not intervene, Carthew said, often allowing strangers to be victimized and, additionally, not stopping friends from committing sexual assaults.

“The Clery Act is really focusing on bystander intervention. And that means that your third parties, your witnesses, other people who are in the area who might witness this. We are really focusing on trying to get them to act,” Carthew said.

Molly Shelton, who is entering her senior year at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, offered her perspective on the college experience and the importance of bystander intervention.

“Whether you’re out at a party and you see someone who’s too drunk or you’re on Facebook and you see a really serious post, you always think someone else is going to respond,” said Shelton.

She said that her sorority, along with numerous other organizations on campuses nationwide, have begun hosting Active Bystander Training courses, in order to instill and encourage attitudes of intervention should a sexual assault occur.

Bystander training alone is worth little without vigilance though, as Shelton recalled an incident where she and other friends found an intoxicated girl lying on the street. They helped her get into a sitting position on a couch to the point where she appeared to be fine, only to find two boys carrying her away towards the end of the night. Pretending to know the girl, Shelton and the others were able to intervene safely on the girl’s behalf.

“If you see someone who’s not okay, even if they say ‘I’m fine,’ go over there and don’t be ashamed to help them because no one else is going to do it,” said Shelton. “You actually could be saving someone’s life.”

The seminar also covered safety from a major emergency perspective, as departing students, like many others, can easily find themselves unprepared in the case of earthquakes and other disasters.

Sandra Gomez, a public health nurse with the Los Angeles County Dept. of Public Health, provided a crash course on emergency preparedness, including what to have readily at hand should the worst occur and how to coordinate with friends, neighbors and family members.

Emergency kits stocked with water, non-perishable food, first aid kit, flashlight, medication, personal hygiene items, cash and more were identified as necessities and Gomez recommended having at least four kits (typically one for home, work, school and in the car). The amount of supplies in an emergency kit should last a minimum of three to seven days, Gomez said, but ideally should provide supplies for seven to 10 days.

Gomez also stressed practicing evacuation procedures “anywhere you consider home,” which naturally would include college dorms. Gomez emphasized mapping out routes for evacuating safely and identifying who can do what in a given group, such as identifying those with medical experience, handiwork skills, and those who may need more help like the visually impaired.

“Stay informed, respond together so that you can do the greatest good for the greatest number of people after a disaster,” said Gomez.

Monday night’s event was the first of a series of seminars CV Weekly will be hosting, covering a variety of topics, including the California drought and local crime.