He swore it was not a setup, just because this was a media interview.

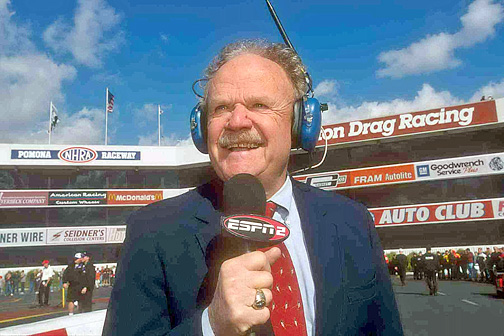

Dave McClelland, sitting outside the Coffee Bean in Montrose, was talking. If you’re not the kind of person who follows motor sports, then you simply might walk by the man and wonder if that guy does any voice work.

But if you are a fan of motorsports, or more specifically, followed the National Hot Rod Association for any time from 1961 to 2003, you might act more like the man standing nearby who found an opening to slip into the conversation on this windy day.

“Dave McClelland,” the man said, with no hint of unsureness as he extended his hand to the 80-year-old retired announcer. “I’m a big fan. I heard your voice and I knew it was you right away.”

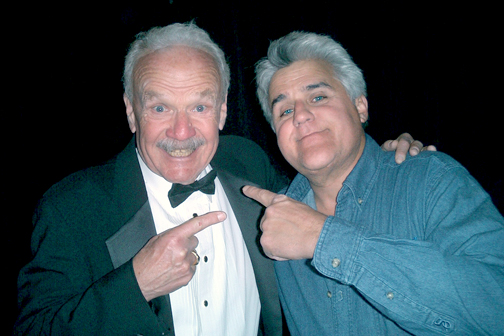

McClelland exchanged pleasantries with the man and then wished him a good day. Then he sort of shrugged. Being recognized simply by the sound of your voice, after all these years, is somewhat common for him.

“You can’t get away,” he said.

McClelland’s career as an NHRA announcer was built on hard work and persistence. He never wanted to get away; he wanted to be a part of the action as much as he possibly could. In June, the man with one of the most recognizable voices in sports, or at least in motorsports, will be one of seven inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America, taking place in Daytona, Florida.

McClelland received the call last November at his home in Oakmont Woods, and said he was stunned.

“When you look at the list of people, you think, come on, they’re not really talking to me. When the guy called, I said, ‘You’re kidding,’” McClelland said.

McClelland will be joined by motorcycle racer Everett Brashear, NASCAR team owner Richard Childress, former land-speed record holder Gary Gabelich, Indy and NASCAR team owner Chip Ganassi,

former IndyCar driver Sam Posey, and former Indy 500 winner Bob Sweikert.

“I think it’s well-deserved. Dave contributed greatly to the sport,” said Steve Gibbs, former vice-president of competition

for the NHRA. “As far as drag racing announcing goes, he’s the best. It’s time for these recognitions to come his way.”

While McClelland may have been surprised at the honor, he has certainly worked hard for it. Growing up in Missouri, McClelland had aspirations to be a football coach. But while at Central Missouri State College, he found out that wasn’t the life he wanted. Instead, he tried his hand in the communications field. It was there he was told his voice, deep and comforting (“I’ve had the same voice since high school”), would more than suit the needs for broadcasting.

He transferred to Iowa State, in the city of Ames, and found himself a booth announcer in radio. It was a comfy, if uninspiring, job. During station breaks, McClelland would step up to the microphone and say, “W-O-I TV, Ames, Channel 5.”

“Then you’d go back, put your foot up and watch the next hour of TV,” he said.

McClelland spent many years in broadcasting, but his passion was always cars. His aptitude tests in school always pointed him toward one thing: automotive mechanic. But one day in 1959, thanks to someone else’s gaffe in the announcing booth, a greater opportunity was handed to him.

It was a drag race between Eddie Hill and Don Garlits. At the starting line, the announcer froze up. McClelland, who was watching with the manager of the track, asked if he could try his luck calling the race. You couldn’t do any worse, the manager replied. McClelland not only worked that race, but he ended up working the whole day.

“I thought, ‘This is really neat,’” he said. “With that, I started looking for places to announce.”

“Dave kind of worked his way through the ranks, and he was blessed with a magnificent voice,” Gibbs said. “He had knowledge of the sport to go along with it. It was only a matter of time before he worked major events.”

McClelland loved drag racing, dating back to his first experience in Kansas City, 1955. It was a new kind of freedom he’d been looking for.

“You could get up close to the cars, up close to the people. There was nobody restricting where you could go,” he said.

And what place hasn’t he been in his career? By his estimation, he’s racked up 3.5 million miles of air travel in the U.S. alone. It is why in 2003 he stepped down as the voice of NHRA, too fatigued from the lifestyle. He has kept himself busy, including working in the master of ceremonies business and doing voice overs for productions.

McClelland’s three children, all graduates from Crescenta Valley High, and he and his wife Louise are more than content to spend their days in the Glendale area. McClelland called his home the wisest investment he has ever made.

As for someone trying to be the next Dave McClelland, the best piece of advice he can give is similar to that of legendary Dodgers’ play-by-play man Vin Scully.

“The most important thing you can do is not to have a good

voice,” he said. “It’s the content of what you talk about. You have to point it toward an audience … that doesn’t understand what you’re talking about. So you almost go back to basics.”

It’s not out of the ordinary for some to bring up Scully’s name when mentioning McClelland. Gibbs didn’t shy away from it.

“For 50 years, he has been the standard that everyone’s tried to live up to,” he said of McClelland. “Of course, nobody compares to Scully, but he was our Scully.”

Scully has a reputation for being more than cordial with fans, and that’s McClelland’s personality as well. He had a friend in motorsports who didn’t like to deal with fans. McClelland told him to be thankful and happy they want to talk to you and shake your hand. McClelland knows what and who to appreciate, because he’s seen and done just about everything.

“When they quit asking to shake your hand, that’s the time you’re in trouble,” he said.