By Sabrina WALENTYNOWICZ

There are some people who run errands on Saturdays. There are some who take it easy around the house. And then there are those who go on cemetery tours. On Saturday, the Historical Society of the Crescenta Valley joined storyteller Nick Smith in offering a free walking tour of the Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena. Smith shared his insights on the many Civil War veterans who are buried there.

Wait – Civil War veterans in California? That was the question on the minds of many in Saturday’s tour group when they arrived at the elaborate front gates of the 131-year-old cemetery.

As many local residents know, the Crescenta Valley was once the destination for people suffering from illness and disease. Many traveled from the eastern United States – including Civil War veterans – who wanted the calm climate and fresh mountain air. Yes, Los Angeles once had the freshest air around!

As the tour wound around a seemingly endless expanse of headstones and looming oak trees, the group learned about some of Mountain View’s residents. One of La Cañada’s first settlers, Civil War veteran Colonel Adolphus Williams, was buried there. He came to California like so many others, with the hope that the fresh air would alleviate his tuberculosis. His tombstone is slightly incorrect, however. The stone reads that he was 52 when he died, but he was actually 49. When his remains were moved to Mountain View three years after he died, he would have been 52 – had he been alive. Discrepancies like this can be found all through Mountain View.

Smith then showed the group a small section of the cemetery where many veterans are buried together. Their graves are small and simple, not unlike the veteran graves at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, DC. Smith said that when a veteran died, he could have a federally issued headstone free of charge. But many found that when the words “federal” and “free” are in the same sentence, the product is sometimes less than perfect. These federally provided headstones were often made without double-checking names and facts, so many of these small markers have a misspelled name. Most do not have dates on them. Some of the veterans died penniless and without families to take care of their burials, so these government headstones were thought to be the solution.

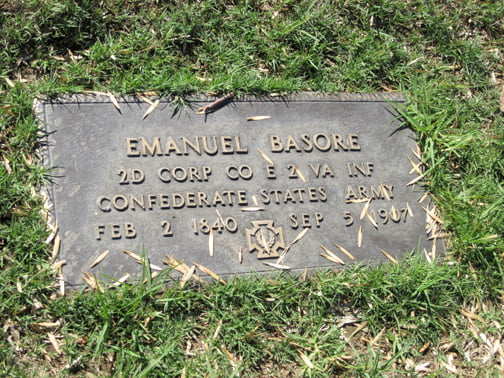

Another problem with burying veterans was determining who was actually a veteran. Smith led the tour to a far corner of the cemetery where Emanuel Basore is buried. His stone lists all of his rankings and which infantry he fought with during the Civil War. But Basore was a Confederate soldier who deserted along with his friend once they realized that they were fighting a losing war. For decades after his desertion, he was not considered a true veteran, and his descendants could not receive any benefits because he left the army dishonorably. It was not until recently, Smith explained, that Basore was recognized as a veteran and received a proper headstone.

There were many such stories and too quickly two hours had passed and the tour was over. The group enjoyed recounting the stories that Smith had shared and many were eager to find another local cemetery for a future tour.

For those reluctant to visit a “dead garden” (as cemeteries can be called), consider a visit akin to a history lesson. Mountain View was a vivid example of how a cemetery can actually bring history alive by sharing the stories of the important people buried who took part in national or local history. And there are also the “average Joes” who might not have an amazing story, but still have a story nonetheless. Take an afternoon and wander the serene grounds, read the gravestones and perhaps the dead will tell you their stories.