Parenthood is tough enough with one baby. But with 100, it will take an entire high school class worth of parents. The Crescenta Valley High School science classes of teacher Christina Engen are currently raising 100 baby rainbow trout to eventually be released back into the wild, and caring for them is more difficult than your average home fishtank.

“It is actually more intense than I realized,” Engen said. “I’ve been wanting to raise trout for a while but it’s a huge funding issue. Then you also have to be approved by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Dept. because it is actually illegal to raise baby trout without [its approval] as [the trout are] an endangered species. So I applied for a 6400 permit, which allows me to transport and rear eggs and fish.”

With the approved permit in hand, it fell to a cost issue. The “several hundred dollar” chiller needed for the eggs was paid for by the CVHS Academy of Science and Medicine and a fishtank was donated. Other aspects, like rocks and thermometers, etc., were provided by Engen. A sponsor from the Santa Clarita Casting Club, a fly fishing group, went down to the Shasta Hatchery to pick up the eggs and they were delivered to the school over spring break.

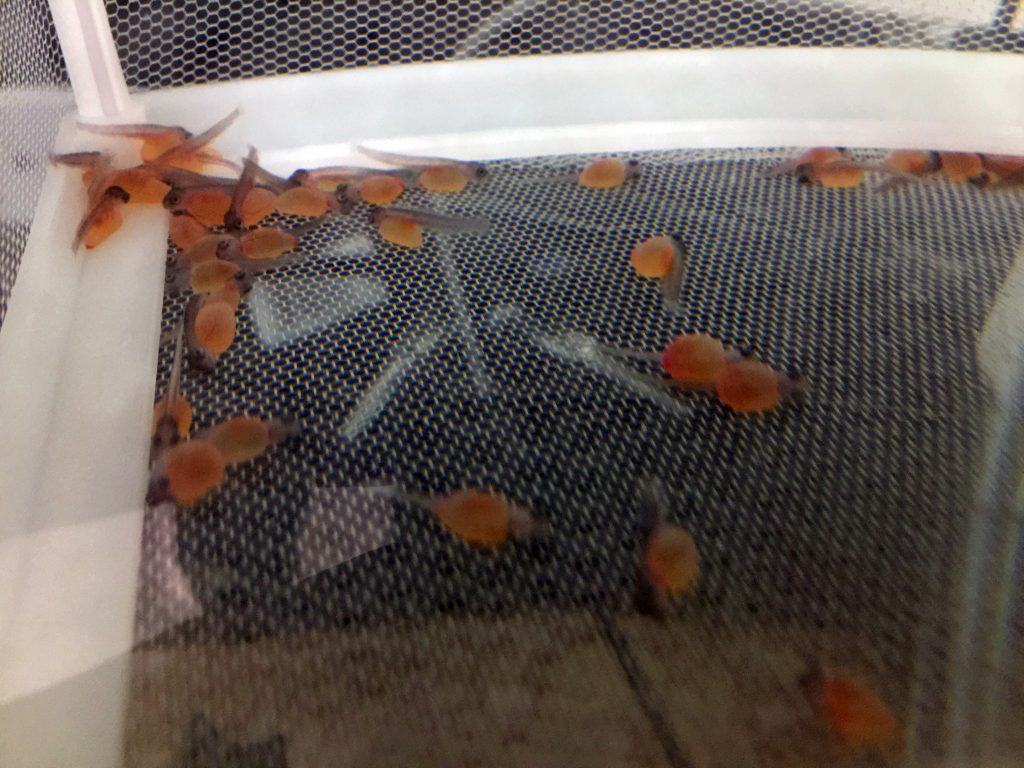

“About a week later they hatched and so we have our larval baby trout. They still have a yolk sac [which provides them nutrients before they learn how to eat what’s around them],” Engen said. “Hopefully they will eat their yolk sacs, turning into fry, which are called small fry, and then we’ll raise them in the tank for another three or four weeks. When they’re big enough to swim, we’ll release them in one of two approved sites – Echo Park Lake or Hansen Dam.”

This exercise provides an opportunity to discuss with her science students the issues surrounding endangered species, life stages of fish, invasive fish, climate change, recreation, urbanization and loss of habitat, and migration barriers like dams. And with the release, they will discuss genetic dilution.

“Both [release locations] are approved because they do not connect to a natural waterway. Since [the trout are] being raised in captivity [U.S. Fish and Wildlife] don’t want to dilute the genetics of the native trout, so we can’t put them in the LA River or anything that goes to the ocean,” Engen said. “One of the big issues with trout species that [U.S. Fish and Wildlife is] concerned about is genetics diluting.”

If all goes well, the trout will be released within three months of arriving at CVHS and another shipment will be scheduled for arrival. According to the permit, the trout can be raised three times a year, with eggs being delivered in January, March and October.