Plastic has only been widely used since the 1950s and yet, in that time, we have produced a staggering 8.3 billion metric tons, reports a new study out of the University of Georgia. That is hard to illustrate in any knowable sense. That is 1.22 billion African elephants. Still not good enough. 22 million Airbus A380 megajets? Still hard to understand. It’s so much that we can’t really compare it to anything knowable. What’s worse is that 6.3 billion tons of that produced plastic has become plastic waste and will take 400 years to break down. Of that 6.3 billion, 9% of the total has been recycled, 12% has been incinerated and destroyed, and the remaining 79% – 4.9 billion metric tons of plastic – is just sitting somewhere in a landfill or as litter.

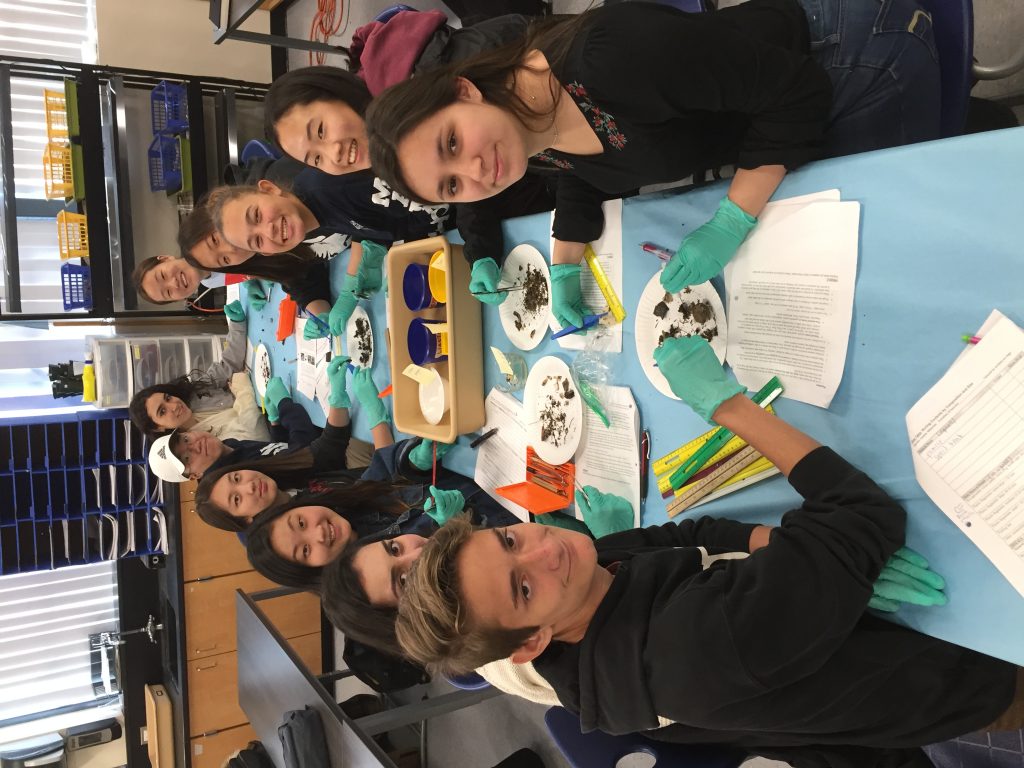

Much of the plastic litter eventually finds its way to the ocean where it is ingested by fish and birds. Scientists are always looking for more data to convince lawmakers that the issue of single-use plastics is a real problem, and now the 11th and 12th grade students of Crescenta Valley High School’s AP Environmental Science classes (right) are contributing to the effort.

“They’re looking at plastic pollution, they’re trying to categorize, basically, how much of the albatross chicks’ diet is plastic. What happens is their stomach fills up with plastic and they think they’re full, so they don’t eat,” said AP Environmental Science teacher Christina Engen, “and then the chicks die, which causes the population to decline. Or the plastic punctures their stomachs and they leak gastrointestinal juices and they die that way.”

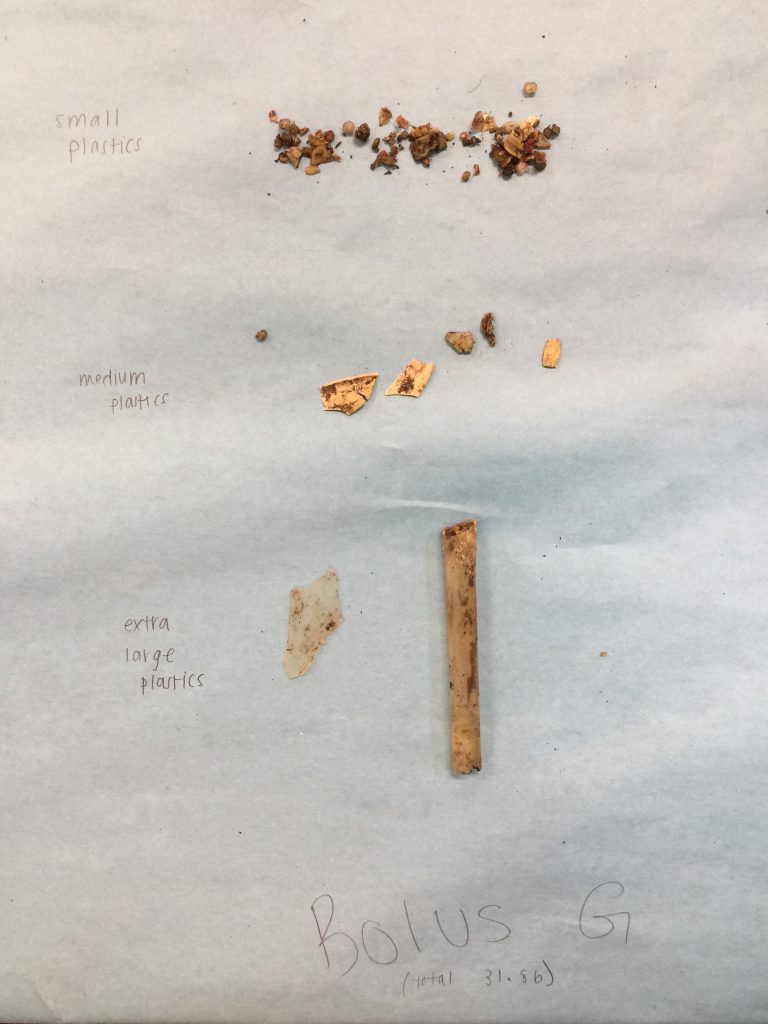

The students analyzed the contents of the albatross stomachs through dissecting boluses, a small, rounded mass of bird vomit that the albatross chicks spit up to clear any blockages. This gives a snapshot of what they eat – bones of fish, shells and more.

“I was very happy to have the vomit. We dissected [the boluses] last month and it went really, really well. We found a lot of plastics. Mussels have spacers in them and we found one of those spacers. We found screening from construction, we found fishing line, lots of little plastic bottle caps [pieces] and things like that. It was really interesting, actually,” Engen said.

These boluses are hard to come by and, after being on a waiting list for almost four years, Engen is pleased to have the opportunity to provide these for her class. They come from Midway Atoll in the South Pacific and are collected once a year by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Dept., and then shared with the schools and organizations that request them. But there is always more demand than available boluses. The data being collected on this set of boluses will be submitted to U.S. Fish and Wildlife to be shared with the scientists compiling the various reports and, hopefully, in two years, when CV is eligible to receive boluses again, they will have another shipment.

“Hopefully [with the data presented], they can get legislation to deal with single-use plastic products to try and get that to decline. Right now there’s a big movement over plastic drinking straws. There’s the campaign #StopSucking and we talk about that as well, and using reusable bottles as opposed to plastic bottles,” Engen said.

She added that she is trying to get the students to understand how using single-use plastic items every day, over the course of a person’s entire life, multiplied by the number of people who make up the human population, which is increasing, causes a huge environmental problem for both the aquatic life and also terrestrial- based life.

“[We’re] trying to get them to make that conscious decision to either use [fewer], or to switch to reusable items,” she said. “That would be the overall goal.”