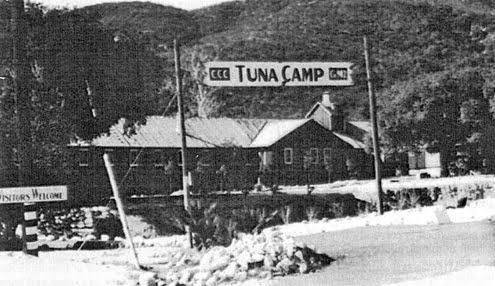

The Los Angeles City Council approved a motion that would set aside a portion of the grounds of the former Tuna Canyon Detention Station site (shown above) for historical status.

By Michael J. ARVIZU

The Los Angeles City Council on Tuesday approved a motion that would allow no less than one acre be set aside for a memorial located in an old oak grove near the site of the former Tuna Canyon Detention Station. The site will be placed on the list of the city’s Historic-Cultural Monuments.

A three-pronged “working group”— comprised of seven members of the community, historians and members of the Japanese-American community; developer Snowball West Investments; and Los Angeles City Councilman Richard Alarcón, who will chair the group — organized by the city’s Planning and Land Use Management committee (PLUM) at its meeting on June 11 will meet beginning next week to discuss the oak grove’s specific boundaries and recommend to the city council the best way to commemorate the historical and cultural significance of the site, located less than a mile from the La Crescenta/Tujunga border.

“We’re going to designate one acre,” said Alarcón. “When the working group comes back in 60 days, it may change. They may make it larger, but they can’t make it smaller.”

The working group will also recommend ways to educate the public on what occurred on the site through the use of plaques, signs and other devices.

“In 2011, when we took over the project, we redesigned the project to save the oak grove,” said Janek Dombrowa, architect for the developer. “We were aware of the history of the site. The trees are probably the best living memorial that we could leave for these people.”

The city council’s motion on Friday overrides a decision by the city’s Cultural Heritage Commission and Planning and Land Use Management committee, which earlier this spring denied Historic-Cultural status for the former United States Japanese internment camp where thousands of American citizens of Japanese descent were sent after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. The decision by the two committees was made on the basis that no buildings from the old camp exist and, as such, they said, no historic declaration is needed.

The Los Angeles City Council, however, argued that there is precedent for declaring a site historically and culturally significant, even if no buildings exist.

“What was more interesting and disappointing to me was that the historic commission said that, because there were no structures, that this site was not significant,” said Alarcón, who in 2012 set forward a motion to begin preservation efforts. “That’s a complete misunderstanding of the history. If we believe that you need to have structures, then we simply do not understand history.”

According to a list provided by the city clerk, 19 historical sites in Los Angeles no longer retain their original façades; other structures have been built in their place. Sixteen sites contain trees or other landscape features.

“What we have an objection to is the council overriding the recommendation of the planning staff and the unanimous recommendation of the cultural heritage commission,” said Fred Gaines, attorney for developer Snowball West Investments. “We ask that you support your PLUM committee, your Cultural Heritage Commission and your city planning staff. What you’re being asked to do today is skip that, don’t follow the law, make findings that no historic expert has made, and put us into a law that doesn’t apply in this circumstance.”

Historical status will allow for federal funds to trickle in that will be earmarked for a possible memorial on the site and interpretive displays, said Sunland resident Joe Barrett.

“The city recognition gives us that go-ahead to make that application for the funding,” he said. “That’s what made it all that important to do.”