By Eliza PARTIKA

Downtown Glendale is now known for its shops, eateries and cars, but in the early 1900s Glendale’s commercial center was mostly citrus fields, railroad tracks, new developments and new businesses.

The fields, farmed by locals and owned by wealthy landowners such as W.C.B. Richardson and L. Brand, yielded fruit renowned for its beauty; so rich was the scent of oranges and strawberries that it wafted for miles. The land, converted almost overnight from dense, coarse brush to sprawling orchards, was advertised often in pamphlets encouraging people to move out to the idyllic hills.

“Once these hills were but sagebrush and desert, but now the productive esthetic orchards and gardens, flower areas, ornaments highways and lovely homes are here to bless and enrapture,” wrote a pamphlet advertising Tropico Beauties, Glendale’s most popular strawberry, in 1923.

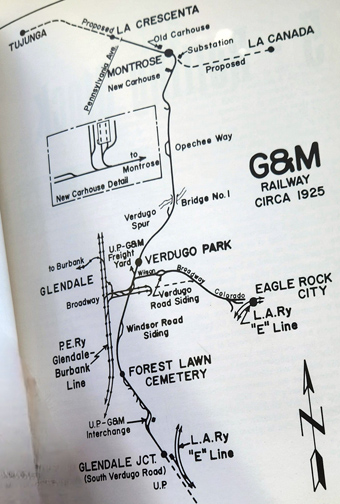

And the railroads were the way to get there – and the way Glendale supported businesses with lumber and freight. The trains and trolleys ran from Glendale to Burbank to Montrose, and another on to Los Angeles. The bustle of the streets supported general stores, restaurants, the Glendale Hotel and hardware stores. Capitol Records had a pressing plant in Glendale that was supported by the rail.

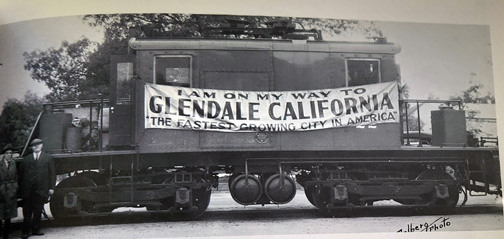

It took many rail lines to support the industry in Glendale. In 1906, there were 2,000 people but in 1930 there were 30,000 – making Glendale the fastest growing city in California for its time.

Michael Morgan, member of the Glendale Historical Society and rail enthusiast, said landowners had a few choices with land as arable as that found in Glendale.

“When you have all this land, what are you going to do with it? You’re either going to make it agriculture, or you’re going to build houses,” said Morgan. “And the way to lure people out West, and move all these people, was the railroad.”

Businesses built in Glendale thrived because of the allure of the railroad, one of the first running into Los Angeles from that location. The current Glendale train depot was built by the Southern Pacific Railroad in the Mission Revival Style in 1923. It had replaced an older depot dating to 1883. W.C.B. Richardson donated part of his land for the rails to be built; the rest of his land was sprawling fields of citrus. The original railroad, which either came up through Brand Boulevard or Glendale Avenue and along the Forest Lawn Cemetery entrance on San Fernando Road, can still be seen today, peeking out of the concrete in front of the far side of the cemetery.

Edgar Douglas Goode of the Glendale Improvement Association convinced Richardson to run a rail line through Glendale. At the time of the original founding in 1883, Glendale was not an officially incorporated city but shared by the city of Tropico. E.D. Goode’s addition of a railroad, as well as the City of Glendale’s control of resources like water to run its city, contributed to the dissolution of Tropico in 1917. Goode, originally from Illinois, moved to Eagle Rock and then to Glendale in 1881. He negotiated the Pacific Electric Railway’s Los Angeles Inter-Urban transit, bringing trolleys to Glendale in 1904. The trolleys ran down Brand Boulevard and up to Glenoaks Boulevard where another line, which Goode also helped found, ran down Glenoaks to Eagle Rock. Between 1909 and 1933, Glendale was the fastest growing city in California. The Glendale-Burbank line, founded by Goode in 1904, took residents from the Burbank area down Pacific Boulevard where, following Glendale Avenue and passing over the Verdugo Wash, the line continued with stops at crossstreets from Doran Street all the way to Maple, Chevy Chase and even San Fernando Road. As they rolled down Chevy Chase, residents and tourists alike would have seen fields of citrus that stretched almost from the rail line to the train depot. The line continued until 1955 when automobiles replaced public transportation in Glendale.

One of the famous residents who was lured to the Glendale-Pasadena area was Henry Huntington. His uncle, Collis Huntington, was in charge of the Southern Pacific Railway and told Henry about the vast opportunities out West. Other notable railway contributors included Eli Clark and Moses M. Sherman, architects of the Pasadena-Los Angeles railway, and J.W.M Burton, who helped build the railway to Montrose.

It was a big deal to go to Montrose in Glendale. Burton’s daughters, Zelma and Emma Burton, would often take their friends to Montrose from Glendale. In 1915, a few years after Montrose was founded, a picture of them and their friends was put into the yearbook.

Sightseers, business people and pleasure seekers coming from Los Angeles would take the line from below Tropico down Riverside Drive and would arrive at Brand Boulevard where they would encounter a bustling Brand Boulevard, hemmed by the original six-story bank building on Brand and Broadway, which still stands today. They would see and smell the citrus for miles. And many who immigrated from states like Iowa, where the luxury of growing lemons or oranges was rare, would decide to put down roots. A company called Mission Pack made it possible for residents to send to their relatives in the Midwest or the East Coast packaged lemons, oranges, and strawberries to enjoy.

Some of the citrus trees and the grandchildren of those original trees can be found in yards around Glendale.