Photos by Charly SHELTON

During its tour, the CVWD reviewed the history of water in the Valley and shared some possible future insights.

By Charly SHELTON

The Crescenta Valley is shaped by water. In a physical sense by the erosion of the mountains by rain, in a cultural sense by the ever-present reminders and memorials of major floods from the 1930s and, more recently, in the 2010s after the Station Fire. In a more basic sense, the settlement here was established around multiple wells and natural springs that flow from the mountain. Water in Southern California is the most precious resource and one that is dwindling as we face the coming aridification of the West.

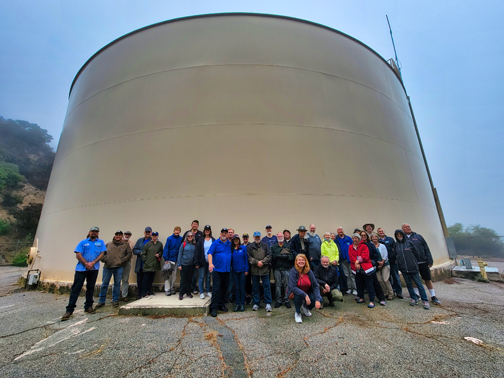

Last week, the Crescenta Valley Water District, in conjunction with the Historical Society of the Crescenta Valley, led a tour of several of its reservoir sites and wells to talk about the past, present and future of water in the Crescenta Valley. Led by David Gould, director of Engineering and Operations for CVWD, the tour consisted of multiple locations across CVWD’s properties in the area, which are usually behind locked fences.

In looking to the past, guests were taken to Pickens Canyon to see a rock tunnel that was cut by hand 500 feet into the mountainside more than 100 years ago. This tunnel leads to a natural spring deep within the rock that is a source of approximately 30,000 gallons of water each day for the CVWD. The water is retrieved from the spring and held in the on-site reservoir tank for distribution to local homes. One home in particular has grandfathered-in rights to the spring and owns 1/12th of the water rights from it so their water is taken directly from the spring and stored in a privately-owned tank for personal use.

For the present, Gould detailed all of the protections put in place to keep the water flowing in case of a natural disaster. These include rubber joints on pipes that flex with an earthquake and seismic sensors on reservoir tanks for shutting off flow in the event of shaking. And beyond natural disasters, the modern conveniences of computer monitoring from the office or from home make it quick and easy to check on water flow levels, cleanliness standards and more. Back in the 1930s, right after the Glenwood Well was drilled at the site of a lake, the operators needed to live on-site to work the machinery and monitor it around the clock. When the larger facility was built in 1972, the houses of the workers were removed to accommodate the facility and, gradually, the off-site monitoring equipment was installed.

Looking to the future, Gould detailed a new project in the works at Crescenta Valley Park. In the Verdugo Wash, an estimated 500 acre feet of water flows through on low-flow days when there is a drizzle, fog or light rain. The suggested project will see inflatable dams installed inside the wash which, during low-flow days, will expand to catch and divert the flow into an infiltration gallery beneath Crescenta Valley Park’s play area and baseball field. This will help to recapture the water into the groundwater basin rather than sending it out through the drains to the ocean. Then, during storms or other high-flow events that have more water than can be absorbed by the gallery, the dams will be deflated to allow the excess water to drain off and keep the flood risk low. Above the infiltration gallery, on the surface of the project area once it is completed, Gould suggests a native garden in the empty spaces around the play area, as well as turning the lower part of Dunsmore Avenue into a green street to allow the rain to seep through the pavement and be recaptured. This project has been in the works for the last 10 years, and the District is currently seeking the proper funding sources for this $4 million project.

This hatch protects the entrance to the tunnel and is only opened by CVWD personnel to check on the spring and perform maintenance.

“However,” Gould said, “what we’re trying to find are partners. The park is owned by LA County Parks and Rec. The streets are owned by the City of Glendale. So we’re trying to work with them and partner them together. And the City of Los Angeles says [it has] rights to all of this water. So right now those are three things that are going on within the park that we’re trying to battle. It’s going a little slower than I’d like it to go, but we’re trying to get it going anyway. This would be a perfect area.”

A recording of this CVWD/HSCV has been made and will soon be available on the CVWD website for any interested residents to view.