Photo by Charly SHELTON

By Charly SHELTON

National Fossil Day is an annual celebration held by the National Parks Service during Science Week to highlight the scientific and educational value of paleontology and the importance of preserving fossils for future generations. It was held on Oct. 13, its 10th year. In honor of the day, a few photos were shared by CVW of the most famous fossil, T. rex. To continue the historical celebration, CVW will present information on some of the fossils that make up the local geology of Southern California.

Now this is a huge task as SoCal has so many different fossils in so many different places. Most will first think of dinosaurs when recalling fossils from a half-forgotten second grade science class, but there is so much more than just dinosaurs in the fossil record – from microscopic life forms that lived 500 million years ago to giant woolly mammoths to ancient humans and human ancestor species. SoCal was underwater during the Mesozoic Era as the T. rex was getting buried in sediment up in Montana, so many of the area’s most notable fossils came from a relatively short time ago – the Pleistocene. The Last Great Ice Age was the era of the saber-toothed cat, mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths and dire wolves. And this is one of the most heavily researched eras of LA’s history thanks to the La Brea Tar Pits, which have trapped a record of life in the basin from about 38,000 years ago. The tar holds the bones, wood, leaves, feathers, exoskeletons and other debris of living plants and animals that got stuck in the tar, which was present and just as exposed back in the Ice Age.

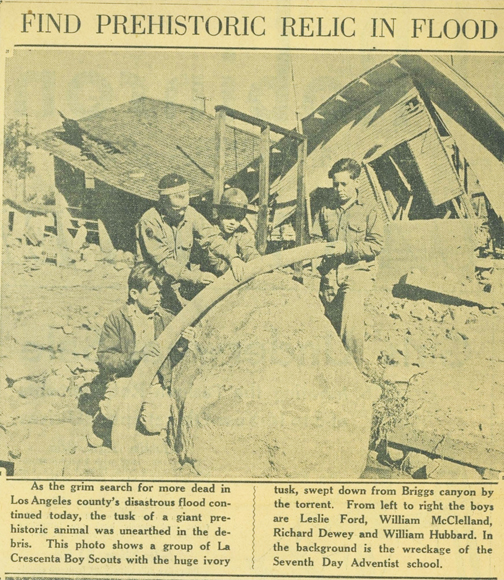

But even without tar pits, fossils abound from that epoch. In the Crescenta Valley, the flood of 1934 loosened a fossil deposit up in Briggs Canyon and a mammoth tusk came washing down the hill. The local paper ran a picture of some La Crescenta Boy Scouts resting the tusk across a boulder in the wreckage of a building.

By the time of the Last Great Ice Age, continental shift combined with the water of the seas being frozen as massive glacial sheets had allowed California to be exposed as dry land for several million years. This sea recession began during the Miocene epoch, which ran from about 5 million years ago to about 23 million years ago, and the seas were just beginning to recede from that continental shift. This was the time when the LA basin was becoming beachfront property. The foothills of the Crescenta Valley were shallow beds of sand, home to clams, oysters, mussels and the like. In Tujunga and Sunland, fire roads cut into hillsides reveal the fossils left over from this time as the land was making its first emergence above the waves. The pearlescent shine of oysters is apparent when the fossils have been doused in water. And the telltale stripes of the clam’s outer shell help to identify the species of clam, many of which are still relatively unchanged today.

What’s interesting is seeing fossils of the Pismo clam, which prefers warmer waters, on the lower part of a trail and then, after climbing higher on the mountain and higher in the layers to younger sediment, to see Razor clam fossils, which prefer colder climates. This change that happens over a period of 15 minutes on a hike took the sediment thousands of years to pile up as the climate slowly cooled around it.

Fossils are everywhere. So in a beautiful place like the Crescenta Valley, keep your eyes open when hiking – you never know what may wash out.