By Robin GOLDSWORTHY

Some describe California as a desert; others as having “a Mediterranean-type climate.” Regardless, California is one of the biggest states in the continental United States with Southern California struggling with ongoing drought conditions.

As water rates continue to rise, the Metropolitan Water District (MWD) – according to its website, Southern California’s largest single contractor of the State Water Project and a major supporter of Southern California water conservation and water recycling programs, along with other local water management activities – recently hosted a three-day excursion to provide insight on where and how local water is delivered to Southern California. The trip was by invitation only for local dignitaries from the cities of Pasadena and Glendale.

First a little background on the MWD. The MWD serves 26 Southern California water agencies and one county water authority. The agencies served are in the counties of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego and Ventura. Water has been imported from the Colorado River since 1941 and from northern California since the 1970s. The recent trip centered on the water from northern California. Among the reservoirs and dams visited was the Oroville Dam located in Butte County.

Oroville Dam has a rich history. Traveling to the Oroville Dam and Visitor Center, remnants were seen of previous gold mines and expeditions – most notably piles of gravel alongside the road.

Extensive security surrounds the Dam, an earth-filled dam on the banks of the Feather River. Construction was completed and the Dam was ready to use in 1968. It is operated by the Dept. of Water Resources and is part of the California State Water Project (SWP). According to its website, the Oroville Dam allocates the flow of the Feather River from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta into the SWP’s aqueduct, which provides a major supply of water for irrigation in the San Joaquin Valley as well as to Southern California. The Oroville Dam is also credited with preventing massive flood damage to the area – an estimated amount of $1.3 billion between 1987 and 1999.

Among the many things visitors to the Oroville Dam will see is its fish hatchery. The hatchery was built shortly after the completion of the Dam because the Dam stopped fish migration up the Feather River when the Dam controlled the flow of the river. The hatchery is an attempt at countering the dam’s impacts on fish migration.

Over the years the Dam has suffered multiple accidents, including cracks in its spillway in February 2017 resulting from heavy rains. Those cracks resulted in the evacuation of low-lying areas (an estimated 180,000 people) due to possible failure of the emergency spillway. Thankfully no failure occurred and after two days people were able to return home.

Many complaints are heard regarding the amount of rainwater that is not captured and ultimately ends up in the ocean. One innovative way the state is combatting that is the creation of the Sites Project.

The Sites Reservoir Project, located northwest of Sacramento, is a proposed off-stream reservoir that would provide 470,000 to 640,000 acre-feet of water storage. (An acre-foot of water is 325,900 gallons.) The massive project would be completed in 2032; however, there are challenges that must first be met before construction can begin. According to Jerry Brown, executive director of the Sites Project Authority, those hurdles include attaining permits and water rights for the portion of the land that is privately held.

“This type of project is not necessarily a model for like projects,” Brown said. “It is limited in scope to being an off-stream reservoir that is locally led.” An off-stream reservoir is not fed by a streambed and is, instead, fed through a pipeline, aqueduct or adjacent stream.

If the Sites Reservoir can be built, according to MWD it would further improve the reliability of the water supply.

The California Delta is another component that supplies water to Southern California as well as the rest of the state.

The Delta, which some estimate at being over 6,000 years old, is formed where the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers meet. According to Curt Schmutte, a consultant with the MWD, the Delta is a resource “that has an expiration date.”

“The Delta is not currently sustainable,” he said pointing to rising seas that increase salinity intrusion and reclamation efforts causing the Delta to sink as primary reasons for the Delta’s expected demise.

Schmutte detailed the introduction of manmade levees, among other factors, as affecting the area’s ecosystem with varying results.

“The fish are starving,” he said.

The Delta is a key part of the state’s economy, serving approximately 30% of Southern California with water. However, aging infrastructure and seismic vulnerabilities, in addition to salinity intrusion and subsidence due to reclamation efforts, are increasing the frailty of the Delta, according to Schmutte.

He noted that the “heartbeat of the Delta is the filling and draining of marshes,” but many of the marshes are becoming extinct. To address this, he suggested producing floating marshes with tule that create refuges for fish and fish food and absorb carbon from the air, then filter it back into the fish food. Though floating marshes are initially expensive, Schmutte feels the benefits are long term. He also suggested re-channeling the water supply and utilizing AI (artificial intelligence) to map out the paths taken by salmon to optimize its survival.

Many Southern Californians though point to the Delta smelt, a small fish that is native to the area, as being a challenge in getting needed water to Southern California.

Schmutte counters that accusation.

“The value of the Delta smelt is not in its singularity,” he said, “but its contributions to the ecosystem overall.”

Schmutte also passed around a sample of a fish screen, a heavy metal structure that is used to protect juvenile fish from entering irrigation channels.

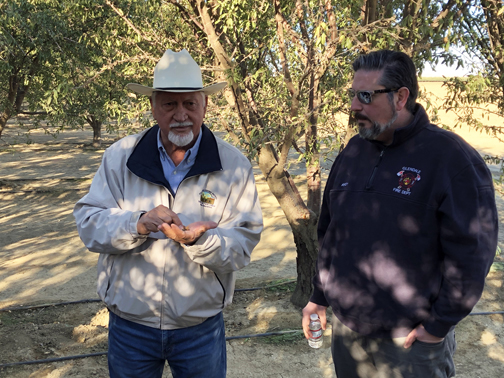

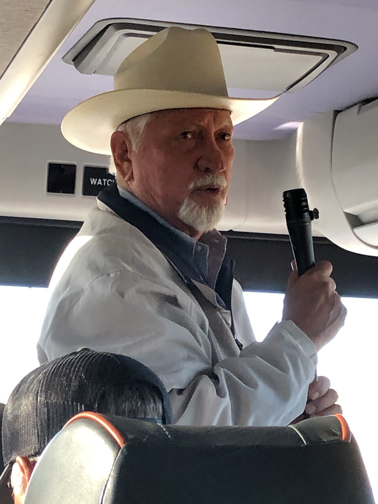

Finally, the situation of California farmers was detailed by Los Banos farmer Joe Del Bosque of Del Bosque Farms.

Del Bosque comes from multiple generations of farmers. He grows melons, nuts and vegetables on the Great Westside of the San Joaquin Valley. He is an advocate for agriculture, water supply and farm workers. He noted the strengths and contributions of agriculture in California and the need for water.

Water availability, he said, can determine the type of crops grown. Those that need more water, for example, might be rejected in favor of those that need less water. He took tour participants to an almond grove that is next to his fields. He explained how the introduction of drip irrigation was a deciding factor in growing certain crops, like nut trees. Some trees have a lifespan of 25 years compared to the 80-day turnaround he sees for his melons.

He also invested in a complex subterranean water irrigation system to mitigate his water use. The use of the technology helps to regulate plantings, the time of plantings and water use, he said.

The climate also affects what can be grown.

“Every Californian should appreciate the climate,” said Del Bosque. “The crops do.”