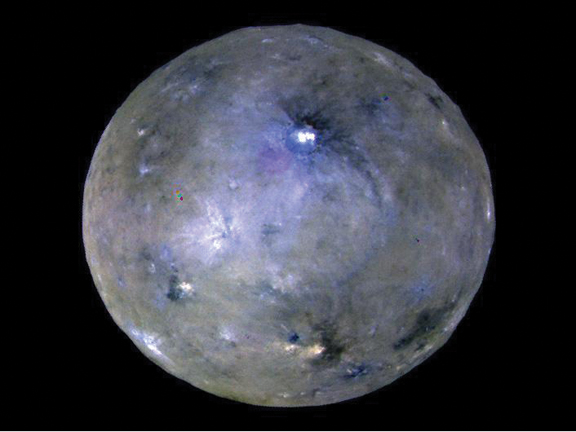

This enhanced color image of Ceres’ surface was made from data obtained on April 29, 2017 when NASA’s Dawn spacecraft was exactly between the sun and Ceres.

By Charly SHELTON

Earth is 4.6 billion years old. That number is nearly unfathomable to the human mind, which deals more frequently in days than in eons. It was so long ago that many of the rocks created in the early throes of the planet’s forming have since been either remelted by another geologic event or completely broken down by erosion, leaving only a few places where such old rocks are exposed to the surface.

Getting a picture of early Earth, on Earth, is difficult. Looking around the solar system, though, there are asteroids and a dwarf planet that are currently how Earth used to be. This was the mission that the Dawn spacecraft undertook – to seek out two of the largest non-planet bodies in the asteroid belt and learn about them now, so that we might see what Earth was and, more broadly, how all rocky planets form. After seven years of study, the Dawn spacecraft ended its mission on Halloween when it ran out of hydrazine fuel.

“Most people think I should be sad it ended. But I’m not sad it ended; I’m thrilled it was so successful!’ said Dr. Marc Rayman, chief engineer and Mission director for Dawn. “Dawn far surpassed all our expectations when we were designing and building it. Under the expert guidance of the Dawn flight team at JPL, it overcame problems in the forbidding depths of space that, by all rights, could have been fatal. It accomplished so much more than we could ever have imagined, including sending us more than 100,000 pictures and other fabulous data. How do I feel? I am elated!”

Dawn was launched on Sept. 27, 2007 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. In July 2011, it reached the asteroid Vesta, second largest object in the asteroid belt. Dawn found that Vesta is the parent of the HED (howardites, eucrites and diogenites) meteorites, which have been striking Earth, and show a similarity to Earth rocks. Dawn traced the origin of these meteorites to Vesta’s large south polar basin where a major event knocked off a piece of Vesta about 1 billion years ago.

In September 2012, Dawn headed off from Vesta to its next destination, the dwarf planet Ceres. This small planet-in-progress yielded a wealth of data for the scientists studying what our planet was like at the “Dawn” of its existence.

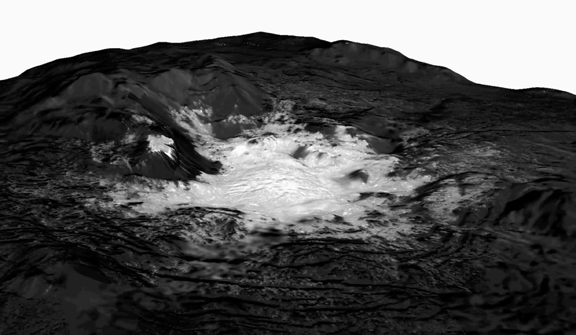

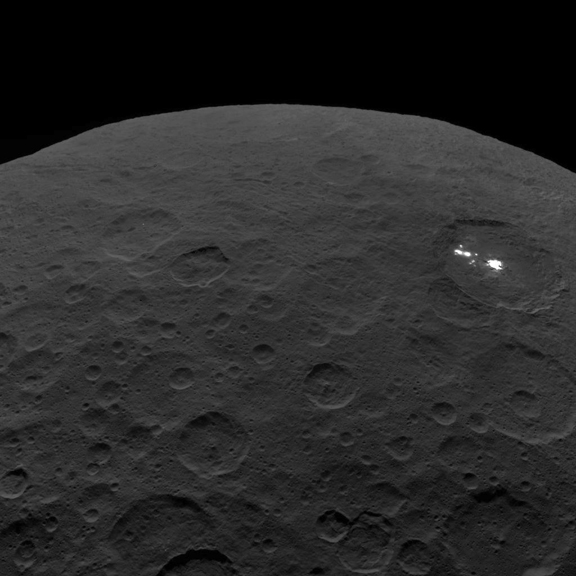

“We learned many important things by exploring the two largest uncharted worlds in the inner solar system. One of the highlights is that dwarf planet Ceres is a geologically active world of rock, ice and salt. It used to have a global ocean and even now may have some liquid underground. We found volcanoes that are not active now but are geologically young,” Rayman said. “We have found mesmerizing bright regions that look as if they are lighthouses casting their beacons over the cosmic ocean, inviting interplanetary ships to go in for a closer look.

“That’s exactly what we did! We found they are formed by salt water that made its way to the surface. The water froze and then sublimated [transformed from a solid to a gas], and it left the dissolved salt behind. The salt is much more reflective than most of the material on the ground, and so it appears bright.”

But all good things must come to an end. Upon arrival at Ceres in 2015, the team encountered issues with the gyroscope-like devices called reaction wheels that allowed for spacecraft movement. The spacecraft had giant solar arrays onboard and this ran most of the spacecraft functions but without the directional shifting power of reaction wheels, the spacecraft couldn’t angle those solar panels toward the sun.

The team was left with a tough decision. It decided to use its onboard hydrazine fuel for maneuvering in lieu of the reaction wheels, but knew this source of fuel was limited.

“When Dawn arrived at Ceres in 2015, we thought the hydrazine might last until early 2016. But the spaceship kept on working efficiently, and we finally recognized earlier this year that it would be depleted in September or October. Dawn operated very smoothly and productively until the hydrazine was fully spent on Oct. 31. It was good to the last drop!”

With the mission at an end and the valuable scientific data safely transmitted back to Earth, it was time to say goodbye. And after 11 years in space and countless hours spent working with the development, execution and function of Dawn, Dr. Rayman had these parting words for the spacecraft:

“Thank you for a thrilling deep-space adventure. You did an outstanding job as one of Earth’s ambassadors to the cosmos. You exceeded all objectives and performed admirably throughout your extraordinary extraterrestrial expedition. We leave you now as a celestial monument to human ingenuity, creativity and curiosity, orbiting one of the alien worlds you unveiled. You will serve there as a lasting reminder that our passion for bold adventures and our noble aspirations to know the cosmos can take us very, very far beyond the confines of our humble planetary home.”

To see some of the more than 100,000 pictures that Dawn sent back, visit Dawn.JPL.NASA.gov.