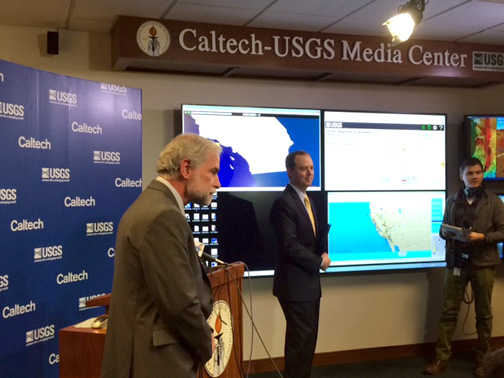

Doug Givens, left, from USGS and Congressman Adam Schiff at Caltech on Monday announced that Congress allocated $5 million in support of the earthquake early warning system.

By Charly Shelton and Mary O’KEEFE

Congressman Adam Schiff was at Caltech on Monday to announce that Congress has included $5 million in a FY 2015 funding bill, also known as the CROmnibus, for a west coast earthquake early warning system.

Schiff and Senator Dianne Feinstein worked together to get the funding secured and, although it is just a “down payment” for what is needed, it is a good start toward a warning system that could give those on the west coast up to a minute warning before an earthquake.

“The annual [cost] is around $16 million with $30 million to $32 million to build out the system,” Schiff said at the Caltech press conference. “We have quite a long way to go. The $5 million is just a down payment.”

He added that the rest of the funding will more than likely not come from the federal government but will have to be sponsored by local state budgets and the private sector which all have a stake in earthquake science.

The annual cost for California alone to operate the warning system is about $12 million.

“The Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA] estimates that the annual losses in earthquakes in the United States is $5 billion a year … so a $5 million investment is quite modest to help protect us from those earthquakes,” said Doug Givens, National Earthquake Early Warning coordinator.

The early warning system is just part of a suite of programs that will help prepare states for earthquakes, including building codes and educational programs.

The earthquake early warning system has been tested for the last three years in a limited capacity and has proven it works, Givens said.

The time from warning to actually shaking will vary from zero to 60 seconds, depending on how far away the quake is.

The system, which relies on posted research points every 12 miles in California, measures earthquakes by detecting P-waves, said Givens.

Earthquakes come in two phases or waves – P-waves and S-waves. The P-wave is the initial slip of the the rock that moves very fast through the crust in a back-and-forth motion. It lasts less than a second and humans usually don’t feel them, but dogs and other animals sometimes can, which led to the urban myth of dogs being able to predict earthquakes. What they are actually detecting is a P-wave.

Following the P-wave comes the S-wave. This wave moves slower and is the up-and-down motion in the crust that causes the actual shaking and all of the destruction that comes with it. The sensors that are used in the earthquake early warning system detect the P-wave and then calculate how far and fast the shaking will occur based on its intensity and point of origin, the epicenter.

“We are building the system on top of the already existing seismic sensors that have run for decades for earthquake monitoring and research and emergency response,” said Givens. “Part of the issue with that network, though, is that many of the existing stations are old and they need to be updated to be fast enough and of high enough quality for use, and we also need more of them because the way you make a system fast is by making sure you have sensors close to where the earthquake is beginning. The further away you are from the beginning of the earthquake, the longer time its going to take to recognize it’s there and start sending alerts. So our target spacing for stations in California is about 12 miles apart.”

“People right at the epicenter will not receive a warning, but those who are farther away can receive several seconds or a minute of warning.

“With advanced notice, people can take cover, automated systems can be triggered to shut down complicated systems and heavy machinery or slow trains, doctors can stop surgeries, firehouse doors can open and more,” according to a statement from Congressman Schiff’s office.

The $5 million announced on Monday is a one-time payment for the system. Schiff said he and Senator Feinstein would continue to advocate in Congress for funding.

“I think further proof of the concept will help drive resources,” Schiff said.

However, Givens said that the science is there and the biggest hurdle to overcome is gathering the funding.

“This isn’t hypothetical,” said Givens. “We have been working on this problem for almost a decade and the project has reached a demonstration phase. So the project, which is called ShakeAlert, began delivering real time alerts to a small set of beta users in January 2012. So the system has been delivering information for nearly three years, and it’s based on pretty well established science at this point. The concept of early warning has been well demonstrated in other countries. They have public systems in Mexico and Japan, so we aren’t way out on the edge of this; in fact we are trailing some other countries.”

Givens said the timing for the system to be up and running will depend on the funding received. From fully funded to operating for the public should take about two years.