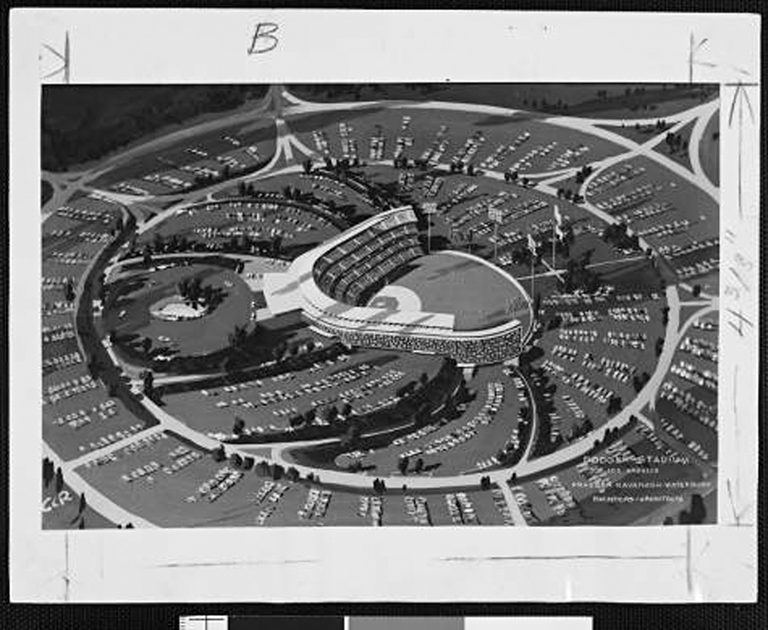

Photograph of an artist’s conception of the new Dodgers Stadium in Chavez Ravine, Los Angeles circa October 1959. Artist’s conception of stadium obtained from the Dodger office.

By Vincent PAGE

When fans of the Los Angeles Dodgers think of the upcoming season, many dream of a parade through LA following a long-awaited World Series victory. The team is still vying for its first title since 1988, and is in prime position after losing in 2017 and 2018 to teams accused of cheating.

There are obvious reasons for optimism with this club. After years of penny-pinching and missing out on top free agents, it finally landed big fish through a trade: former MVP Mookie Betts and former Cy Young Award winner David Price. This takes a team that won 106 games last year and puts it as the favorite for the World Series. The team could be so good that the record for wins in a season (116) might be in its sights come September. There are no holes on this roster, but rather superstar after superstar at nearly every position.

Whenever that World Series victory does come it will be another installment in covering up the horrific and ugly history of how baseball came from Brooklyn to Los Angeles.

Chavez Ravine wasn’t always just a nickname for Dodger Stadium. For the first half of the 20th century, the hilly area was home to many Mexican-American families who were kept out of other communities through methods including redlining. Chavez Ravine was a place where many families lived and, while outsiders viewed the community as a ghetto, the citizens of Chavez Ravine formed a close bond. They depended on each other. They grew their own produce and raised their own livestock. An elementary school and church in the area further deepened the community’s bond.

However, the city of LA considered the land that these families called home underdeveloped, and introduced a plan for a large public housing project in the early 1950s. The city immediately began offering payment to the homeowners in Chavez Ravine. The initial offers weren’t fair financially. Most families refused. But the city came back and began forcing some families out. For others, the offers began getting lower and lower. People sold their property out of fear they’d eventually be forced out with no financial compensation at all.

By the mid-’50s, the public housing plan had fallen apart. Nevertheless, fewer than two dozen families remained in Chavez Ravine.

Years later, the city sold the land to the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. In return, the Dodgers traveled 2,800 miles westward to their new home in sunny Los Angeles.

First the city came to Chavez Ravine with financial offers. Then they came with bulldozers and police.

On the day known as Black Friday by families formerly living in Chavez Ravine, the few remaining residents ¬– men, women, and children – were forcibly carried out of their homes with their furniture. Mere minutes later, all they could do was stand and watch as their homes and the elementary school the kids attended were demolished and buried to build Dodger Stadium.

Some families decided to camp in tents around their demolished lives. Abrana Arechiga, who had lived in Chavez Ravine for 45 years, told reporters, “We started in a tent then and maybe we’ll end in a tent.”

Though all the families eventually left the area, the hardship of having their homes demolished left an intense impact on them. Aurora Vargas felt abused by the city, stating, “I think they did that to scare the other homeowners not to fight. And they didn’t. We were the example.”

She would spend 30 days in jail after having a nervous breakdown thought to be due to the violence used by the city to force the families from the area.

While the site of former homes of thousands of people may be hosting a World Series come October, don’t forget how LA’s beloved Dodger Stadium came to fruition. Only through the city’s intimidation of Mexican-Americans, financial manipulation of the poor, and, eventually, brute force did one of LA’s vulnerable communities become an icon for the sports world.