Thar She Blows! Round After Round – Now No One Knows

After more than 15 years of effort to acquire the needed permits, a small army of bulldozers arrived on scene. Spreading out across the 200-acre plain they got right to work on the grading laid out in the master plan. After weeks of work, all was going smoothly until one operator noticed a colleague examining something. Suddenly she began waving her arms. Under the loud rumble of his machine, he could just make out her shouts: “Stop! Stop the dozer!”

He brought the behemoth to a halt, cut its engine and hopped down from the cab to see what the fuss was all about. As he approached others were gathering, each gazing downward. Arriving on the spot he leaned forward and there before him was something he’d never seen before. It was time to call the M. I. B.

Within hours, a 1964 champagne beige Cadillac DeVille departed from the Los Angeles Natural History Museum. These mobile investigators of bones were responding to a call emanating from the construction site of the Angeles National Golf Club in Sunland.

It was 2002 and, after years of preparation, construction had recently gotten underway. When the two investigators arrived on site they were met by the project supervisor who was eager to lead the way. After several minutes of traversing over a moonscape of bulldozed terrain, they finally came upon it: a large oval sandstone boulder, five feet long, four feet wide and three feet high, imbedded with light-colored inclusions.

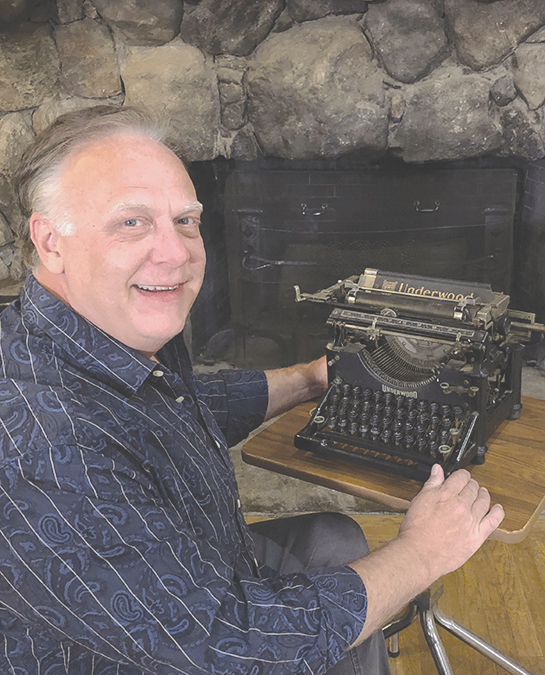

These two fossil hunters included Howell Thomas, the more seasoned of the duo, and his younger sidekick Doug Goodreau. Within the sandstone matrix their experienced eyes resolved the bone material of an ancient whale. To be more specific, they identified the rear portion of a whale’s skull and some bits of upper vertebrae exposed at the surface.

There are two families of whales. Mysticetes, which use baleen plates in their mouths to sieve planktonic creatures from the water, and Odontocetes, the toothed whales. Due to Howell’s many years of experience he determined this animal was of the baleen type. This played a major role in what transpired next.

A decision had to be made as to what to do next and there were many considerations that were taken into account. A primary factor was the potential for knowledge advancement. It turned out that numerous baleen whale fossils had been discovered in Los Angeles and therefore many similar specimens were already in storage, awaiting examination. Because of this, the decision was made to leave the fossil in place.

At the time, there was talk of acknowledging the fossil but during the intervening 20-plus years all memory of the remains had been lost, including the location. This required a present-day attempt to relocate the whale of the wash.

Doug recently returned but found the area unrecognizable and could not relocate the boulder. So I headed out to begin my search. That day the manager of the golf club wasn’t on-site, so this first leg of my exploration was cut short. It was then I became obsessed with seeking out the great white whale bones.

Returning days later I was surprised when the manager presented me with a golf cart to pursue my quarry. Soon I was sailing through a sea of fairways, sand traps and greens. Unfortunately, after hours of searching I was unable to locate the lost fossil.

Some millions of years ago a shallow sea extended into our valley. A whale took its last breath there, sank to the sea floor and was buried by sediment. The bones fossilized, the land was uplifted and eventually this piece broke from the rest of the skeletal remains and during a flood event was transported down the Big Tujunga River to where it now lies.

I will return and maybe I’ll get lucky next time and exclaim, “There’s Bogey Dick!”